Unlike the fireworks-filled celebrations seen in many countries, the Japanese New Year (Oshogatsu・お正月) is a time of reflection, family, gratitude, and beautifully symbolic food(Osechi・お節).

It is one of Japan’s most cherished holidays!

- A Fresh Start: How Japan Celebrates the New Year

- How to Visit a Japanese Shrine: A Simple Guide to Proper Etiquette (Especially for New Year!)

- ✨ Why This Matters During New Year (Hatsumode)

- Closing Thoughts

- Osechi Ryori (お節料理): New Year’s Food with Meaning in Every Bite

- Traditional Osechi Dishes and Their Meanings

- Why Do People Eat Osechi?

- Modern Osechi

- Conclusion

A Fresh Start: How Japan Celebrates the New Year

✨ 1. Cleaning the home (Osoji・大掃除)

In late December, households perform a deep clean to wash away misfortune from the previous year and greet the new one with purity.

I usually start November to clean the households, because it takes a lot of energy and times.

And it is usually the job for woman, I do it all by myself 🙁

It is a very HARD WORK!

✨ 2. Decorating the entrance

Traditional decorations include:

- Kadomatsu (門松): Bamboo and pine arrangements that invite the gods of good fortune. (Not everyone decorate this one recently, because it costs a lot)

- Shimenawa (注連縄): Sacred rope hung above entrances to ward off evil spirits.

I buy Shimenawa every year!

✨ 3. Visiting shrines (Hatsumōde 初詣)

On January 1–3, people visit shrines or temples to pray for health, prosperity, and good luck. Long lines, food stalls, and festive energy make this a memorable event!

If you gonna visit shrines, there are rules you should know!

How to Visit a Japanese Shrine: A Simple Guide to Proper Etiquette (Especially for New Year!)

Visiting a Shinto shrine, especially during New Year’s hatsumode (初詣) is a beautiful way to experience Japan’s spiritual culture.

1. Enter Through the Torii Gate

As you approach the shrine, you’ll pass under the large red or wooden gate (called Torii・鳥居)that separates the everyday world from the sacred world.

Etiquette:

- Bow once before entering.

- Walk slightly to the left or right of the center; the middle path is considered the kami’s (deity’s) path.

(But if the shrine is very famous one, there must be a lot of people on new years day, so you should listen to the security person or adjust to others)

2. Purify Your Hands and Mouth at the Chozuya (Temizuya・手水屋)

Before approaching the main hall, visitors perform a small purification ritual.

It’s not about physically cleaning, it’s about purifying the heart and mind.

Steps:

- Take the ladle with your right hand, pour water over your left hand.

- Switch hands. Clean your right hand.

- Pour water into your left hand (not directly into your mouth) and rinse your mouth quietly. (After CONVID, rinsing your mouth is Forbidden)

- Rinse your left hand again.

- Hold the ladle vertically so the remaining water washes down the handle.

- Return it face-down.

This ritual is called temizu (手水) or chozu.

3. Approaching the Main Hall (Haiden ・ 拝殿)

Once purified, walk toward the main hall respectfully.

Tips:

- Remove hats.(Many Japanese especially younger people not remove hats recently though)

- Keep voices low.

- Photography is usually allowed, but some inner areas may restrict it.

4. The Offering and Prayer Ritual

This is the part many visitors worry about, (Actually I do worry to because it is just once a year thing for me) but it’s easy!

You should watch people before you, they do the same, you can learn:)

The Standard Shrine Ritual:

- Throw a coin into the offering box (usually a 5yen coin for good luck! I throw 50yen usually).

- Bow twice.

- Clap twice.

(This calls the deity’s attention.) - Make your wish or offer thanks silently.

- Bow once more to finish.

This is called “ni-rei, ni-hakushu, ichi-rei” (二礼二拍手一礼).

Note: A few shrines use slightly different methods, but this is the common one.

5. Ringing the Bell (If Present)

Some shrines have a large rope at the front.

Ring the bell before bowing and clapping to announce your presence to the kami.

6. Drawing Omikuji (Fortunes)

After praying, many people draw omikuji (おみくじ) — paper fortunes.

If it’s a good fortune:

- Keep it!

If it’s a bad one: - Tie it to a designated rack or tree to leave the bad luck behind.

- It will cost about 100yen~200yen.

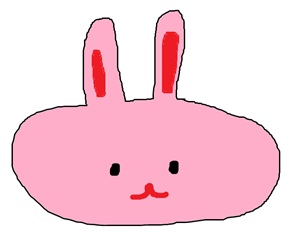

7. Amulets, Charms, and Returning Old Ones

Shrines sell omamori (お守り) , protective charms for health, love, study, and more.

- Old charms should be returned to the shrine at the end of the year for ceremonial burning.

- New charms are purchased for the coming year.

- It will cost about 1000yen~5000yen usually.

I usually get Omamori for study and I’ll put it on my randoseru(a traditional Japanese school backpack).

8. Exiting the Shrine

- Walk calmly back toward the torii.

- Bow once again after passing through the gate.

This marks your return to the everyday world.

✨ Why This Matters During New Year (Hatsumode)

Millions of people visit shrines between January 1–3 to:

- Give thanks for the past year,

- Pray for health and luck,

- Buy new charms,

- And enjoy food stalls and festivities.

Knowing the basic etiquette helps you enjoy the experience and makes the moment feel even more meaningful.

Many people also visit shrines for Hatsumode (New Year’s shrine visit)wearing kimono. It’s very colorful and festive, and I highly recommend it if you have the chance!

Since putting on a kimono can be difficult, I suggest going to a beauty salon that offers kimono dressing or using a rental service.

Closing Thoughts

Visiting a shrine isn’t about strict rules, it’s about showing respect and taking a quiet moment to reflect.

Understanding shrine etiquette adds depth to the New Year experience.

Osechi Ryori (お節料理): New Year’s Food with Meaning in Every Bite

Osechi Ryori is a beautifully arranged set of traditional New Year dishes, usually served in stacked lacquer boxes called jubako (重箱).

Each dish has a symbolic meaning, often related to health, longevity, prosperity, or fertility.

It’s like eating good luck for three days straight!

My Jubako is like this one below ↓

The reason I chose this jubako is that the crane is a symbol of long life, making it not only beautiful but also meaningful.

Traditional Osechi Dishes and Their Meanings

1. Kuromame (黒豆) — Sweet Black Soybeans

Symbolizes health, hard work, and diligence.

To “work hard like a bean” is a good thing in Japanese culture!

2. Kazunoko (数の子) — Herring Roe

Represents fertility and prosperity in the family, thanks to the many tiny eggs.

3. Tazukuri (田作り) — Glazed Sardines

Originally used as fertilizer, these fish symbolize abundant harvests and prosperity.

4. Datemaki (伊達巻) — Sweet Rolled Omelette

A fluffy, sweet omelette roll that stands for knowledge and learning, because its rolled shape resembles old scrolls.

5. Kamaboko (かまぼこ) — Broiled Fish Cake

The red-and-white color symbolizes purity, protection, and celebration.

6. Kuri-Kinton (栗きんとん) — Sweet Chestnut Mash

Bright golden in color, it represents wealth, good fortune, and economic success.

7. Nimono (煮物) — Simmered Vegetables

Lotus root (with its holes) symbolizes clear vision, burdock root for stability, and carrots cut like flowers for happiness.

Why Do People Eat Osechi?

Osechi was originally designed to be prepared before New Year’s Day so that:

- Families could rest from cooking,

- Kitchen fires could be avoided (historically considered unlucky),

- And everyone could spend the holiday relaxing and sharing meals.

Even today, many families order gorgeous osechi sets from department stores or restaurants—some costing hundreds of dollars!

I usually make Osechi by myself and I have to start making it 12/30 every year.

Modern Osechi

While traditional dishes remain beloved, modern osechi may include:

- Roast beef

- Western-style desserts

- Seafood gratin

- International flavors

This fusion approach helps younger generations enjoy the tradition in a contemporary way.

Conclusion

Japanese New Year is more than a holiday, it’s a moment of renewal, tranquility, and gratitude.

And Osechi transforms the start of the year into a delicious wish for happiness, health, and good fortune.

Whether you’re celebrating in Japan or simply curious, exploring Osechi is a beautiful way to experience Japanese culture from the dining table.

コメント